Boom in Aging Adults Could Overwhelm Mental Health Care Field

Lounging on a beach, listening to waves gently crash on the sand under the warmth of the Floridian sun is a pretty mental image for many 30- and 40-year-olds stressed out by the daily grind of their unrelenting schedules. But for adults aging into retirement, transitioning from their fast paced careers into much slower lifestyles can lead to mental health challenges as they’re left asking, “What do I do tomorrow?”

Paul Gionfriddo, president of Mental Health America, says that the harm of untreated situational depression cannot be downplayed for older Americans.

“My suspicion is, in future generations, we’ll continue to see more people who are diagnosed with depression at later ages who’ve never been diagnosed before simply because the environments in their lives have changed,” Gionfriddo says.

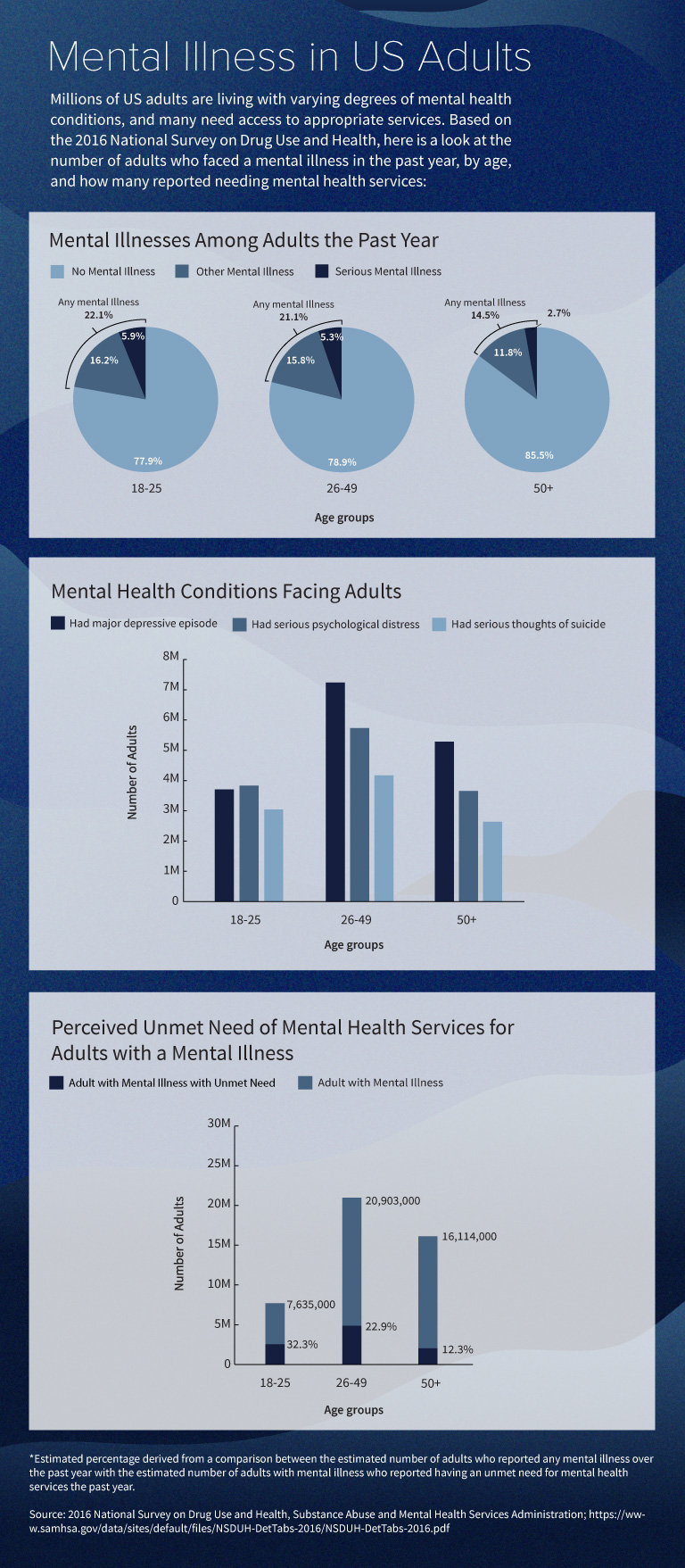

That could pose a serious problem for the mental health care system as the American population grows older thanks in large part to the aging baby boomer generation. The U.S. Census Bureau predicts that almost one in five U.S. residents will be 65 years or older by 2030. And approximately one in four adults ages 65 or older has some type of mental health problem not associated with aging.

Text-only version of this image.

As Americans live longer and the overall population ages, the mental health care field will need to be better equipped to treat a population that is more likely to experience mental illness in their lifetimes and more likely to be newly diagnosed as an older adult.

A Perfect Storm for Baby Boomers

A 2015 Gallup poll found that 21 percent of baby boomers were diagnosed with depression during their lifetimes, a higher rate than all other adult age brackets. Gionfriddo says that a perfect storm of circumstances leaves the baby boomer generation susceptible to mental health concerns.

Between 1970 and 2015, the overall U.S. life expectancy has increased from approximately 71 years to 79 years. People in general are living longer, including those who have experienced mental illness thanks in part to more sophisticated and successful treatments for their conditions. Unlike the generations that came before them, they are aging into the 65 years and older bracket having lived with mental illness and are being joined by adults who are being diagnosed with a mental illness for the first time.

Historically, isolation, loss of loved ones, and medical problems contribute to the deterioration of mental well-being as people age. But Gionfriddo points out that confronting retirement at a time when they aren’t sure that they want to stop working has been particularly tough for this generation. Many baby boomers aren’t ready to leave behind leadership roles, high-powered jobs, and high pressured circumstances which give them a sense of value and purpose.

“People feel much younger at the age of 65 today than 65 year olds felt a generation ago,” Gionfriddo says. “It’s a generation that isn’t ready to retire. It wants to stay in shape and it wants to stay active.”

These concerns are coupled with economic anxiety about whether they can afford retirement. A 2017 USA Today survey of adults ages 45 to 65 found that 77 percent believe that they should be saving more for retirement. And more than one in four reported having no retirement savings.

Breaking Down Barriers

In 2015, about 56.5 percent of adults with mental illness did not receive treatment. Baby boomers may not seek help due to fear that people will view them differently and that they could experience discrimination, Gionfriddo says.

“It’s not as destigmatized as say the flu and yet for many people it’s almost as common as the flu,” he says. “This creates a real barrier for people who have been told that mental illness is a weakness and not simply a health condition that’s easily treatable.”

Mental Health America is also vigilantly combatting the myth that mental illnesses such as depression are a natural part of aging. While depression may co-occur with other conditions associated with aging such as chronic disease, these health challenges are separate and should be treated separately.

Although many adults continue to forgo necessary treatment, there have been bright spots that could point to a more positive outlook for baby boomers. For example, while baby boomers reported the highest rates of depression among all adults, that same Gallup poll found that approximately 14 percent of baby boomers were being treated for depression, also the highest rate among all adult groups.

Dr. Eric Beeson, a core faculty member at Counseling@Northwestern, believes that the move toward integrated health care will help to reshape the narrative around mental health and reduce stigma for this generation. Many doctors’ offices are now incorporating behavioral health, mental health, and physical health into a one-stop-shop that allows older patients to receive their yearly physical, while also being screened for mental health conditions, creating a seamless transition for patients.

“People don’t see it as separate as much anymore. They see it as an integrated holistic process,” Beeson says. “It’s more OK to ask for help. And when they receive a recommendation from their primary care doctor with whom they have a longstanding relationship, they are more willing to listen to that as opposed to independently reaching out to a mental health professional.”

However, as the aging population becomes more comfortable seeking out screenings and treatment for mental health conditions, the question will then become whether the mental health field is prepared to handle the influx of potential patients.

“The mental health field is aging itself. And what we haven’t had is a significant inflow of younger persons and professionals in mental health,” Gionfriddo says. “I think that’s going to present a problem because there will be relatively fewer places for baby boomers to turn.”

Currently, more than 100 million Americans live in areas with a shortage of mental health care workers. Those numbers could get much worse. The National Center for Health Workforce Analysis consistently found shortages in the projected supply of behavioral health practitioners by 2025. For example, the demand created by the growing and aging population could lead to a shortage of mental health and substance abuse workers anywhere from 17,000 workers to as high as 50,000 workers.

Filling the Gaps

“We have a unique set of professional values that are grounded in human development and wellness,” he says. “Our professional values and our traditions are really aligned well with the integrated whole person health care movement as well as the care of older adults.”

Clinical mental health counselors are eligible for licensure and to diagnose and treat mental health disorders in every state and are eligible to receive reimbursement from other federal programs such as Tricare. For Beeson, expanding their practice to cover the Medicare-eligible population is the next logical step.

“A clinical mental health counselor can work with an older adult and be reimbursed all the way up until they are Medicare eligible,” he says. “All of a sudden a client ages into the Medicare system and their services can’t be reimbursed. That creates a significant rupture in their care because patients have to go see another provider or they have to pay out of pocket for that service that they have been receiving from the same provider for 10 years.”

To help push for changes to Medicare law, the American Mental Health Counselors Association (AMHCA) advocates for the passage of the “Mental Health Access Improvement Act.” Beeson believes strong advocacy is sustenance for the counseling profession and warns against the consequences of being left out of Medicare reform and general health care reform.

“Without continued advocacy we will not remain a profession at least as we are currently,” Beeson says. “Our ability to diagnose and treat mental illnesses, our ability to receive reimbursement, our ability to receive suitable reimbursement rates—all of these things are threatened every year in state legislatures.”

An updated Medicare system, he says, will ultimately work better for aging patients which should be the priority for mental health care policy.

“We have to look at this from a logistical and pragmatic perspective. If there is more access to providers, then older Americans are more likely to receive the care that they need especially in areas where access may be limited. Adding clinical mental health counselors to this policy increases mental health care access and ensures the continuity of care.”

Citation for this content: Northwestern University’s Online Masters in Counseling program.