Addressing Suicide Among First Responders: How Colleagues, Friends, and Family Can Help

Whether they’re running into burning buildings, engaging an active shooter, or navigating crowded streets at high speeds on the way to a hospital, first responders often put their lives at risk as part of the job. And while they may recognize the inherent danger, firefighters, police officers, and emergency medical services personnel sometimes fail to consider the toll it can take on their mental health.

In 2017, more firefighters and police officers died by suicide than in the line of duty, according to a report by the Ruderman Family Foundation. The report estimated that at least 103 firefighters and 140 police officers died by suicide, while 93 firefighters and 129 police officers died in the line of duty. And those numbers may not tell the whole story. Only 40% to 45% of firefighter suicides are reported, according to estimates by the Firefighter Behavioral Health Alliance (FBHA).

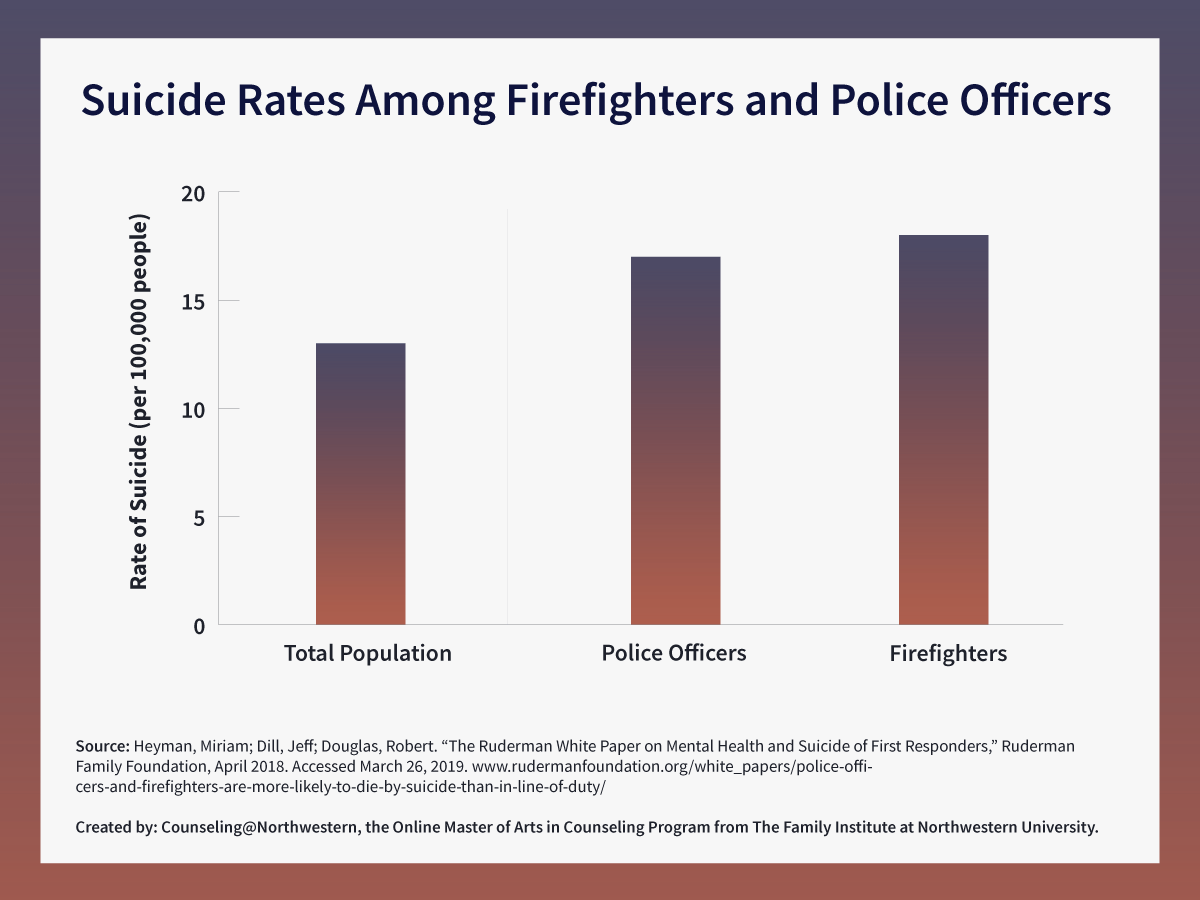

The rate of suicide was 18 per 100,000 people for firefighters and 17 per 100,000 people for police officers. Comparatively, the rate of suicide for the total population was 13 per 100,000 people.

Those are “very concerning numbers,” said Dr. Nate Perron, core faculty member at Counseling@Northwestern, who has expertise in police and first responder wellness. “But it shouldn’t be as terribly surprising as we would initially think.”

Those who are responsible for helping us at our most vulnerable points are hurting, too. And it’ll take the work of friends, family, and colleagues to help keep them safe.

Why First Responders Are at Risk for Mental Health Conditions and Suicide

First responders, who include police officers, firefighters, medical personnel, disaster relief workers, and coroners, typically arrive early to incidents involving harm to people or property, (PDF, 269 KB) according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The nature of their work exposes them to death, grief, injury, pain, and loss, coupled with demanding schedules, physically challenging job requirements, and a lack of safety and security in certain work situations.

Repeated exposure to death and destruction can result in emotional trauma, which can lead to mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, PTSD, and, in the worst cases, suicide.

How First Responders Develop Serious Mental Health Issues

Exposure to

death, grief, injury, pain, and loss

↓

Coupled with

demanding schedules, physically challenging jobs,

and a lack of safety and security

↓

Can result in

emotional trauma

↓

If left untreated, can lead to

depression, anxiety, PTSD, suicidal ideation, and suicide

FHBA founder Jeff Dill, who is a licensed counselor and retired fire captain from the Chicago suburbs, stressed that it doesn’t take a huge tragedy to affect a first responder. Mass shootings or natural disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina, are acute events that can cause PTSD, but a person could be affected by cumulative work exposure to smaller incidents.

The Ruderman report notes that poor mental health can prevent first responders from completing their duties and remaining attentive to the task at hand. For example, PTSD has hindered first responders’ abilities to accurately assess risks, plan responses, and focus on more than one problem at a time, such as multiple victims in an accident. Stress can create physical responses in the body that cause responders to be less capable of completing the tasks associated with physically demanding jobs.

There is also no defined timetable for when exposure to trauma begins to cause serious mental or emotional harm.

“Even senior officers who have not shown signs [of depression] in the past can certainly have reactions or responses that, to them, seem like very confusing feelings of despair,” Dr. Perron said. “A situation that suddenly reminds them of their own grandchild who just passed away or a circumstance that reminds them of some tremendous grief or loss that they haven’t dealt with can certainly affect them.”

Many first responders forgo seeking help for mental health issues, which can put them at risk for developing more serious conditions that lead to suicide. Miriam Heyman, senior program officer at the Ruderman Family Foundation and co-author of the report, spoke with Jay Ruderman on his podcast about the barriers first responders face when seeking mental health treatment.

“These are professionals who explicitly prioritize bravery and toughness, and putting others before themselves, so there’s this perception within these departments that to speak out about your own struggles is selfish and is contrary to your job description,” Heyman explained.

She also noted that many have a legitimate fear of being discriminated against if they do speak out.

“Mental health is a prerequisite for becoming a police officer, and folks fear that if they speak openly about anxiety or depression, they might lose their weapon, they might be told that they have to retire, and that’s not entirely fictitious. That has happened,” Heyman said.

Barriers to Mental Health Treatment for First Responders

The Ruderman Family Foundation report classifies barriers to addressing mental health into three groups:

Cultural Barriers

- Strength, bravery, and resilience are revered.

- Silence about mental health issues leaves responders feeling isolated.

- Responders perceive their colleagues to be more judgmental than they are.

- Responders fear speaking out will limit career advancement.

Lack of Awareness

- People lack knowledge about mental health and the conditions that should cause concern.

- Shame, fear, and embarrassment contribute to stigma.

- The media does not cover first responder suicide or mental health, which creates the perception that there is no problem.

Pragmatic Barriers

- Responders have limited access to services.

- Costs for treatment can be high.

- Erratic work schedules leave limited time to seek treatment.

How to Help First Responders in Need of Support

Through Nationwide Chaplain Services, Dr. Perron has provided mental and emotional support to police officers in the Chicago area. He participated in ride-alongs to get to know officers on their turf in a way that made them more comfortable and enabled him to better understand their needs.

“We spend so much money making sure that officers have the correct armor and the correct weapons to keep them safe and other people safe. How are we arming them emotionally and mentally?” he said. “First responders are people that need to be armed in the same way–holistically.”

Dr. Perron shared his thoughts on how workplaces, colleagues, family, friends, and individuals can prevent mental health conditions from worsening and leading to suicide.

Workplaces and Colleagues

Police departments, fire departments, and emergency medical systems need to prioritize the importance of preserving mental and emotional health to make it easier for first responders to access available support.

“When the chiefs call me, I tell them they have to work on two things: You have to work on your peer support and your resources,” said FHBA’s Dill, whose organization consults with fire departments nationwide.

Dr. Perron said agencies can support the mental wellness of their employees and volunteers by:

- Having the police chief and fire chief talk about mental health and the importance of going to counselors. Having open and honest discussions is key.

- Placing a mental health advocate or someone in local precincts and firehouses who is made available to talk to in a comfortable way.

- Having management check in regularly with workers.

“Being able to process a traumatic incident is increasingly recognized as such a crucial and important element in being able to support officers, firefighters, and EMT personnel,” he added.

When a traumatic incident or tragedy occurs, Dr. Perron encourages first responder teams to implement the Critical Incident Stress Management System. This system of education, prevention, and mitigation of the effects of highly stressful incidents is helpful for officers to talk about problems they are having.

Friends and Family

Family and friends often recognize their loved one is showing symptoms of stress before the first responder. If a first responder disengages with their community outside of work, that can be an early sign of trouble.

“If there is a display of unsafe behavior or erratic behaviors, loved ones need to be very clear that these are some of the things that are not healthy,” Dr. Perron said.

To provide support, he encourages family and friends to:

- Be clear about concern regarding problematic behavior they notice. Clarity in communication is important.

- Encourage an individual to seek help and offer to help them find treatment such as counseling.

- Push back on notions that getting mental health treatment will affect the person’s job.

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention provides loved ones with a list of risk factors and warning signs loved ones should be aware of if they are worried.

The Individual

Everyone must be aware of what they need—physically, mentally, socially, and spiritually.

“Ultimately, all of us need to make sure that we are well-balanced in all of these different areas of our lives,” Dr. Perron said. “If even one of those areas is quite significantly impaired, it can really affect all the other areas.”

First responders should ask for help if they begin to experience the following warning signs:

- Depression or anxiety.

- Feelings of despair with life.

- Inability to concentrate or make decisions.

- Changing or increased drinking habits.

- Thoughts of self-harm.

- Thoughts of hurting other people.

Mental Health America offers screening tools to help self-identify symptoms of mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD. The Firefighter Behavioral Health Alliance also provides a self-screening for suicide ideations.

If you or someone you know is in immediate need of help, the following hotlines assist first responders and their families:

- Safe Call Now: Call 1-206-459-3020 for a 24/7 hotline staffed by first responders.

- Fire/EMS Helpline: Call 1-888-731-3473 to reach this help line run by the National Volunteer Fire Council.

- Frontline Helpline: Call 1-866-676-7500 for a 24/7 line staffed by first responders and run by Frontline Responder Services.

Additional Support

To learn more about what is being done to address the mental health needs of first responders, visit the following organizations:

Citation for this content: Northwestern University’s online Master of Arts in Counseling program.