Inspiring Addiction Recovery Through Community Change

The day he was arrested felt like the end of the world. But years later, Eric Beeson, Counseling@Northwestern faculty member and researcher, considers it to be one of the best days of his life. It was the moment that everything changed.

On July 21, 2006, Beeson’s life came crashing down around him when he was arrested while struggling with an active substance use disorder. As a result, he was fired from his job where he was trying to help others with an issue he had yet to recognize in himself.

“Some people enter the counseling field because they have their own unresolved issues to work through, some of which they aren’t even aware of. For a professional counselor, being honest with yourself in active self-reflection is so important,” Beeson said. “You really have to do your own work first, and you can’t do your own work vicariously through the work of your clients. It just doesn’t work that way. It’s harmful for you. It’s harmful for your clients.”

Shortly after his arrest, a pastor friend showed him a scripture passage: “You were once shown compassion so that you can show compassion to others in a similar way,” it read. Although he doesn’t prescribe a particular religion, those words left an impression.

“That really stuck with me, and it’s become a mantra that I try to live out not only in my personal life, but also in my life as a clinician, as an educator, and as a researcher,” Beeson said. “When I’m slipping, I remind myself of this passage to anchor in that mindset of giving back and being compassionate to others as well as myself.”

Personal experience, formal clinical training, and the call to pay it forward now fuels his passion for recovery advocacy and research.

“It is an honor and privilege for my personal and professional lives to coexist in such a way,” Beeson said. “I am so grateful, and with this comes a responsibility to be a face and voice of recovery because if we don’t talk about this process, then who will?”

The Role of Recovery Capital

According to Beeson, recovery is about much more than sobriety. It is a process of living with a new purpose in pursuit of wellness, quality of life, and sustained recovery.

“There are many pathways to addiction and many pathways to recovery,” he said. “Treatment needs to be personalized and address the complex biological, psychological, and social factors that lead to each pathway.”

Beeson said professional counselors can aid in this process by focusing on the development of “recovery capital”—the internal and external resources people have access to as they initiate and sustain recovery. Researchers such as Robert Granfield and William Cloud have divided recovery capital into four categories: social (e.g., support from family); physical (e.g., health care and money); human (e.g., education and health); and cultural (e.g., values, beliefs, and attitudes). Capital in each group is extremely helpful in initiating and sustaining the recovery process.

“Unfortunately, recovery capital is not equally distributed,” Beeson said. “Certain populations have access to more resources than others.”

Go to an accessible version of How Privilege Can Impact Addiction Recovery.

To fully consider these four categories, clinicians use assessment tools. One tool is the Recovery Capital Scale, which measures the quantity and quality of resources and support that those in treatment have at each stage in their recovery.

For example, an addiction can be fueled by a biological predisposition.

“Some people are born more likely to develop an addiction than others through no fault of their own,” Beeson said.

He suggested that although someone might not intend to misuse substances, something as simple as having surgery that requires prescription pain medicine can activate a genetic predisposition to addiction, almost like “flipping a switch.” Once the prescription runs out, people with addiction will go to great lengths to find additional substances to curb cravings and manage withdrawal. If opioids become harder to get, people might use other substances like heroin to cope.

Regardless of the path that may lead someone to addiction, once a person initiates use, there is a strong neurobiological process that is hard to break.

“The body does not like when those drugs are taken away,” Beeson said. “It creates this preoccupation to engage in that behavior.”

After repeated use, the brain is hijacked and higher-order decision-making is suppressed. Then, according to Beeson, substance use can become reflexive.

“We don’t yell at our knee when we hit it and it kicks up,” Beeson said. “So, can we blame people when they act on a reflex to use a substance?”

Beyond biological components of addiction, helping people with substance use disorders to develop human capital is in a counselor’s wheelhouse. This means they help clients build resilience, grit, and self-efficacy while enhancing hope and self-esteem. However, human capital can’t be addressed without considering a person’s access to social and physical capital.

Social capital is very important, as Beeson knows. When he was arrested and booked, Beeson’s father bailed him out of jail. His father also provided him with a place to live and helped him retain a lawyer, get into treatment, and find a new job—critical components that gave him a stable foundation to begin his recovery.

“I had no plans to quit using drugs when I was arrested, but those resources gave me the opportunity to give it a shot and to explore some of the underlying contributors to my substance use,” Beeson said. “If I didn’t have access to those resources, I don’t know where the heck I would be.”

Without this capital, Beeson said he could have sat in jail for 30 days, fueling his anger and frustration, which may have encouraged his substance use after being released.

The different forms of capital are highly connected to privilege, which plays a significant role in recovery and, in Beeson’s opinion, something that isn’t discussed enough.

“It’s not news that certain populations are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system and are treated very differently by some members of law enforcement,” he said. “My own privilege as a white male afforded me a lot of opportunities to navigate the criminal justice system in a way that other people might not have had.”

Beeson recalled during his arrest when an officer asked him to raise his hands and get out of his car. When he reached down to open the door, he was greeted with a gun in his face. He wasn’t injured, but wondered, “What would have happened had I not been a white male?”

Changing the Treatment Paradigm

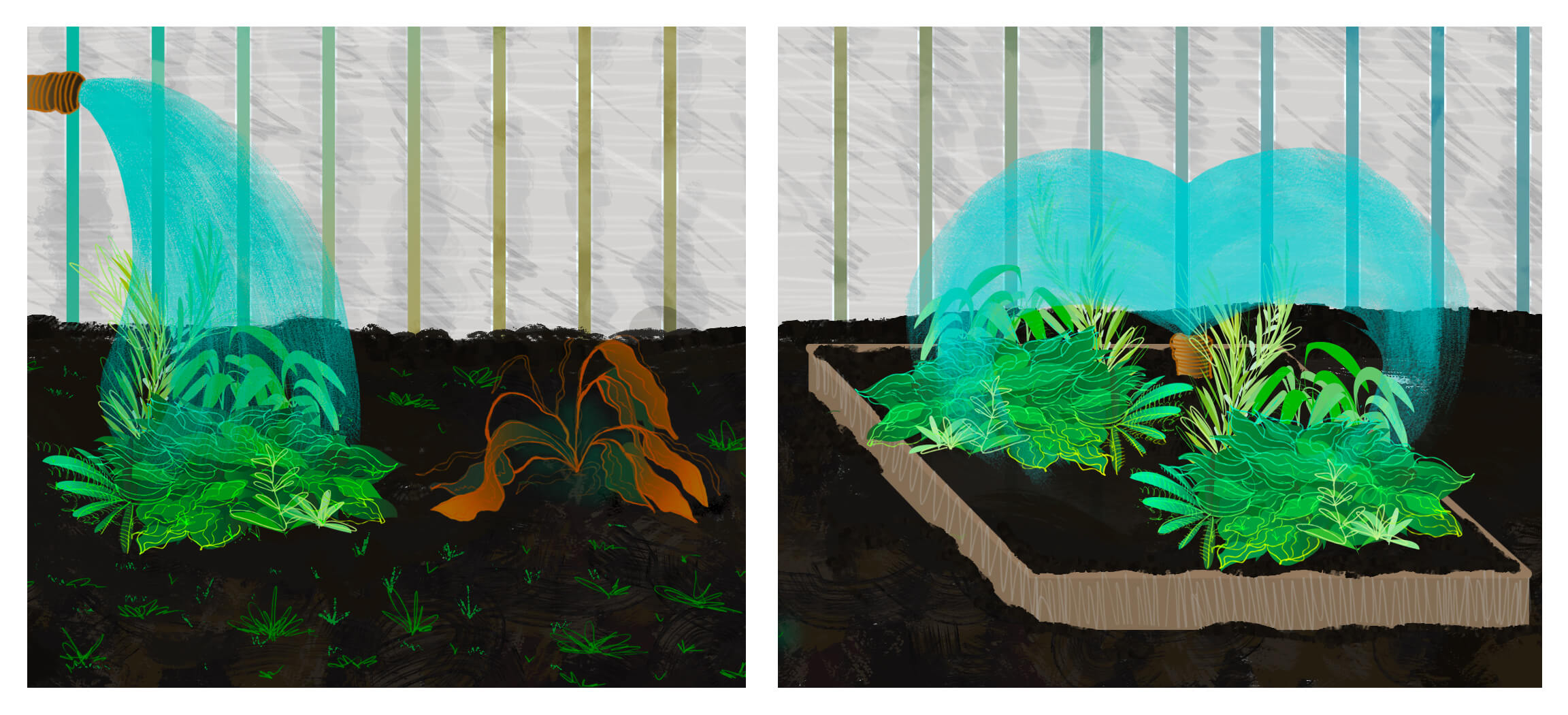

The illustration above demonstrates the differences between individual care and systems transformation. On the left, the plant that receives acute care (active but short-term treatment) is healthier, but the other plants in the garden remain unhealthy because they lack root-level nourishment. Because the garden contains malnourished soil and is unhealthy overall, the healthier plant that receives care may eventually also become unhealthy. On the right, the plants are watered regularly and evenly via a sprinkler system, with continued care and support. This nutrient-rich garden system is transformed and ensures long-term, sustained growth. Like the illustration depicted above, when an individual receives treatment and returns to a community that does not offer the necessary care and support, they too may become unhealthy, returning to their previous level of functioning. However, a systems transformation can help to sustain recovery.

Beeson said the traditional addiction treatment paradigm focuses on a “treat ’em and street ’em” approach that places those struggling with addiction in clinical care until they’ve detoxed in the short term. The problem with this acute care model is that it fails to address the long-term implications of addiction. Once people are placed back in their original environment, they are exposed to the same conditions that fostered their addiction and then are shamed when they return to use.

That is why Beeson said he believes treatment needs to be holistic and employ a chronic-care model. He said treatment paradigms need to be inclusive and move away from the idea that addiction is the fault of individuals and that it’s their responsibility to get better on their own. Specifically, people with substance use disorders need to be a part of the solution.

“There is a growing peer-support movement that treatment providers need to be aware of,” Beeson said. “And the treatment community needs to use these incredible resources during treatment and into after-care.”

Beeson said the power of recovery advocacy can’t be understated.

“I used to be ashamed of my addiction, and I didn’t like to be labeled as an addict, but I didn’t know any other way to talk about it,” he said. “I also experienced significant barriers to employment and licensure as a result of my criminal record and past substance use.”

Luckily, there has been tremendous growth in recovery advocacy efforts over the past decade that have given people in recovery a voice and the tools to become strong advocates for new systems of care that are recovery oriented. Beeson said training he received from Faces & Voices of Recovery, which promotes long-term recovery through advocacy and education, significantly altered the quality of his recovery.

“I internalized stigma and believed I would always be less than because of my past,” he said. “But when I went to this training, I learned about a new way to talk about recovery, in a way that was positive, affirming, and hopeful.”

The training, titled “Our Stories Have Power,” moves past doom and gloom discussions about addiction. It elevates the experiences of people recovering as they strive for improved quality of life. Unfortunately, some treatment providers are not aware of this messaging and often talk about clients in ways that could promote stigma, Beeson said.

Beeson also urges counselors to consider wellness and human development from a public health perspective. Counseling is not just about developing health and wellness at an individual level. He said the core identity of professional counselors prepares them to be social justice advocates, putting them in a position to strive for systems transformation.

“There is a growing peer-support movement that treatment providers need to be aware of.”

— Eric Beeson, Counseling@Northwestern faculty member and researcher

Another leader changing treatment paradigms from a systems wellness perspective is Don Coyhis, founder and president of White Bison Inc., an American Indian/Alaska Native nonprofit. His concept of “Wellbriety” is a substance addiction recovery and healing program that grew as a response to intergenerational trauma in Native American communities.

Wellbriety promotes healing root problems within communities in order to help individuals recover. It is this approach that inspired the vegetable garden depiction of systems change in Figure 1.1. When explaining this concept, Coyhis uses imagery of a sick and dying tree to illustrate a person struggling with addiction and a forest to illustrate the community they were born into. In an interview with Sharing Culture, Coyhis explained the concept of the Healing Forest:

“Suppose you have 100 acres full of sick trees who want to get well. If each sick tree leaves the forest to find wellness and then returns to the forest, they get sick again from the infection of the rest of the trees. The Elders taught us that to treat the sick trees you must treat the whole forest—you must create a healing forest. If not, the trees will just keep getting sick again.”

According to Wellbriety’s training booklet, “Unless individuals, families, and communities are provided with a means of overcoming the impact of the unhealthy, dysfunctional root system (anger, guilt, shame, and fear), they will find themselves participating in unhealthy behaviors.”

Shifting to a recovery-oriented system of care is one way the counseling profession can move toward healing through wellness promotion and share the responsibility of developing holistic change with the broader community. Going through recovery can be a strength, which a person can grow from. Beeson emphasized that not only is it possible to sustain recovery, but also that someone can thrive in recovery.

“My recovery has blessed me beyond measure and allows me to be an active participant in the lives of my family and my community,” he said. It has also opened the doors to opportunities he says he never would have known to dream of before his recovery, such as becoming a licensed professional counselor and teaching at Northwestern University.

Beeson’s history with addiction and recovery helps him connect to his work in a deep and meaningful way. Reflecting on that pivotal day of his arrest, Beeson said it was the shock he needed.

“I knew I couldn’t do it on my own, and it was going to take something significant for me to consider recovery,” he said. “My arrest took away many of the things that I thought were important to me and gave me the opportunity to achieve things that truly are important.”

If you or somebody you know needs help with a substance use disorder, connect with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Helpline by calling 1-800-622-HELP (4357)

Citation for this content: Northwestern University’s online Master of Arts in Counseling Program.