Pushing Back on Perfectionism: How to Be Happily Imperfect

Considering a Career in Counseling?

No matter how little academic or professional counseling experience you have, you can make a difference as a mental health counselor through our Bridge to Counseling Program.

Perfectionism is ingrained in American culture. We’ve devised athletic competitions, educational standards, and work environments that reward flawless performances. Olympic gold medalists, perfect test scorers, workaholic CEOs worth billions—they enthrall and inspire us.

While the human drive for perfection can be a catalyst for success, pushing too hard over time can be destructive, say mental health experts.

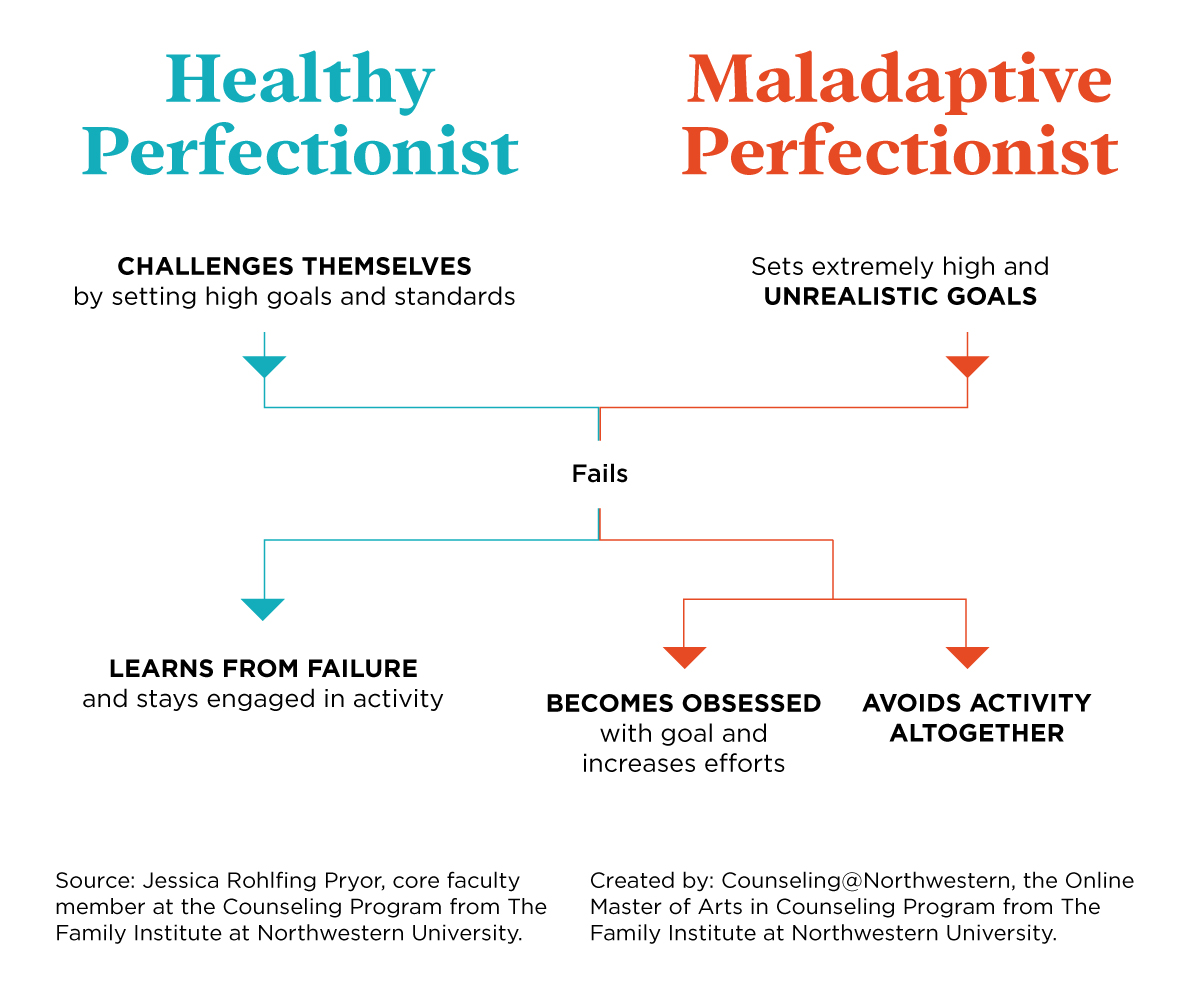

“Perfectionism is a pretty sophisticated construct. Generally, it has an adaptive or healthy side and a maladaptive or unhealthy side,” said Dr. Jessica Rohlfing Pryor, core faculty member at Northwestern University’s Counseling Program from The Family Institute.

Striving toward high standards or goals in a healthy manner can provide a challenge, strengthen us, and be part of the learning process, says Dr. Pryor, who studies perfectionism at Northwestern’s Perfectly Imperfect Lab. But when they fail, healthy perfectionists have an ability to bounce back rather quickly and are able to stay engaged even through performance setbacks.

Perfectionism becomes unhealthy—called maladaptive perfectionism—when there’s an unrealistic attempt at reaching excessively high or impossible goals.

An example of maladaptive perfectionism: “Feeling a pressure to be the best at everything. For example, being the number-one student athlete and the valedictorian and getting into the ‘best’ university,” said Pryor. “One person’s ability and energy to obtain, let alone remain at, that level of excellence over a long period of time—that’s impossible to do.”

With maladaptive perfectionism, the goals aren’t just high; they’re impossible to achieve. For that reason, failure is often guaranteed, said Pryor. Failure experiences can be very painful to people with maladaptive perfectionism. If they lack the resilience that a healthy perfectionist has, they may respond to setbacks with either goal obsession or goal avoidance.

“A top priority becomes avoiding failure at any cost,” she said. “For some, that means they may double or triple their efforts toward the goal. But then others may go to the opposite extreme and avoid the experience or task altogether.”

Among maladaptive perfectionists, there’s often a belief that if they don’t hide their mistakes, their manager, professor, or partner may not admire them or may not think they’re good enough, Dr. Pryor added.

“This is a pretty miserable way to function, all of these things combined. It’s pretty rough, and really with the best of intentions to do well, many individuals get caught in this type of imperfectionism,” she said.

Is Perfectionism on the Rise?

In a 2017 study, researchers examined perfectionism among college students in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom over the past three decades and found that three types of perfectionism have increased among recent generations of students.

Self-oriented perfectionism: Individuals attach irrational importance to being perfect, hold unrealistic expectations of themselves, and are punitive in their self-evaluations.

Associated with: negative physiological reactions to life stress and failure, clinical depression, anorexia nervosa, and suicidal ideation.

Socially prescribed perfectionism: Individuals believe their social context is excessively demanding, that others judge them harshly, and that they must display perfection to secure approval.

Associated with: anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation to greater degrees than those with self-oriented perfectionism.

Other-oriented perfectionism: Individuals impose unrealistic standards on those around them and evaluate others critically.

Associated with: higher vindictiveness, hostility, and the tendency to blame others, in addition to lower altruism, compliance, and trust.

What Factors May Be Contributing to the Rise in Perfectionism?

Authors of the study point to four cultural factors that may be exacerbating the desire to be perfect among younger generations:

Competitiveness:

Young people are preoccupied with upward social comparison, experience considerable status anxiety, and value materialism. They are also more dissatisfied with who they are, worsened by exposure to others’ seemingly perfect self-representations within social media.

Individualism:

Younger generations report higher levels of narcissism, extroversion, and self-confidence. They spend less time doing group activities for fun and more time doing individual activities for instrumental value or sense of personal achievement.

Meritocracy:

Innate personal value is measured by educational and professional achievement, status, and wealth. Young people are taught that the principles of meritocracy are fair and are compelled to demonstrate their merit by setting increasingly unrealistic goals and defining themselves in terms of personal achievement.

Parental practices:

Pressure to raise successful children in a culture that emphasizes monetary wealth and social standing has increased anxious and controlling parenting. Parents pass their own achievement anxieties on to their children, encouraging children to adopt extremely high standards to avoid criticism and gain the approval of their parents.

How to Tell if You May Be an Unhealthy Perfectionist

With the help of Dr. Pryor, Counseling@Northwestern compiled a list of questions to ask yourself in order to reflect on whether you’re trying too hard to be perfect. If you answered yes to many of these questions, you may be developing traits associated with unhealthy perfectionism.

However, these questions are only meant to be a non-clinical self-assessment of perfectionistic characteristics. For an accurate assessment, you should reach out to a mental health specialist who can evaluate your needs and provide the appropriate treatment.

- Do you worry about what others will think if they saw who you really are?

- Do you feel as though the better you do, the better you are expected to do?

- Do you put off starting or finishing projects, wanting to get them just right?

- Do you find that you are never satisfied with your accomplishments?

- Does your family/partner expect you to be perfect?

- Do you push people away in order to avoid rejection?

- Do you feel that something only counts if it’s done perfectly?

- Does failure raise your expectations of yourself even higher?

- Do you “collect” your failures and mistakes in a mental archive?

- Do you feel that others are too demanding of you?

- Are you highly self-critical?

How to Cope with Perfectionism

Dr. Pryor describes maladaptive perfectionism as an “epidemic.” And while people may not be able to eliminate all of their perfectionist tendencies, they can take steps to address the negative aspects of perfectionism that have detrimental effects on their lives, she says.

Below, Pryor shares strategies that can help people better understand, avoid, and scale back unhealthy perfectionism.

- Remember: Perfectionism is an “absolute illusion.” People are barraged throughout the course of their lifetimes with distorted messages—from parents, teachers, peers, and broader sources (e.g., entertainment, social media)—that nothing but the best is good enough and that perfection is possible.

- Break goals into bite-size pieces. Perfectionists may become overwhelmed by the size of a goal, such as planning a wedding, studying for college or graduate school exams, or taking on a new work project. Break down big-picture goals into smaller, manageable chunks and celebrate each smaller accomplishment.

- Interrupt the self-critical voice in your head. Replace it with a positive statement, or try to redirect your thoughts to more constructive thinking. Tell yourself, “It’s okay if this isn’t perfect.”

- Do something positive for yourself. In a moment of stressed-out, perfection-seeking behavior, try to press pause. Practice relaxed breathing, or take a walk if possible. Stay grounded in your five senses. Then allow yourself to reflect on this question: “What will happen if I’m not perfect?”

- Use a mantra. Develop a positive mantra such as, “You are enough” or “Your best is enough,” and say or think the phrase at times of stress.

- Recognize it may be in your genes. Some research shows that perfectionism has biological components and may be linked to genetic markers. Acknowledging that your perfectionism may be inherited can help push back against negative feelings of self-blame.

- Reach out to a professional. Pryor’s research shows that individuals with maladaptive perfectionism are less likely to seek out help from family and friends or professionals. If you are suffering from perfectionism, talk about it; seek counseling. Reach out to friends, family, or your health care provider if you need assistance finding a counselor and don’t know where to start.

- Stick with therapy. Perfectionists tend to skip out on therapy before they get into the real dirt, which is related to their need to avoid showing others flaws and imperfections—and the belief that if they do, people will think less of them.

- Recognize that you are modeling behavior for others. If your teen or preteen is exhibiting unrealistic goal setting, they could be learning these behaviors from you. Check your own tendencies and practice positive behaviors together to help them normalize their feelings and “boss back” negative self-criticism.

To learn more about perfectionism and to stay up to date on Dr. Pryor’s latest research, visit The Family Institute’s Perfectly Imperfect Lab, which predominantly examines maladaptive expressions and features of perfectionism and their implications for interpersonal functioning.

Citation for this content: Northwestern University’s online Master of Arts in Counseling program.