Supporting the Physical and Mental Health of New and Expectant Black Mothers

She’s a sports icon still at the top of her game. As one of the most celebrated athletes in the world, she’s in peak physical condition and knows her body well. Still, that wasn’t enough for doctors to believe Serena Williams when she told them she needed a CT scan after giving birth, worried that her shortness of breath could mean she was having a pulmonary embolism. Doctors eventually acquiesced. Williams was right to be worried—small blood clots had settled into her lungs, the tennis star recounted in an interview with Vogue.

“Unfortunately, this speaks to a cognitive resistance—a term coined by Dr. Derald Sue—that is demonstrated by health care professionals and has longstanding historical context for people of color and in this case, Black women,” said Dr. Tonya Davis, clinical training director and core faculty for Counseling@Northwestern, the online Master of Arts in Counseling program for The Family Institute at Northwestern University.

Like Williams, many Black women face serious challenges with pregnancies—and all too often their concerns are dismissed, minimized, or invalidated by health care professionals. Williams survived childbirth, but many Black women do not.

According to an article from ProPublica on child birth, maternal mortality rates for all women in the U.S. have steadily increased since 1990. In 2015, there were approximately 26.4 deaths per 100,000 live births. The U.S. has the highest rate of maternal mortality for all developed nations, even as rates of infant mortality fall.

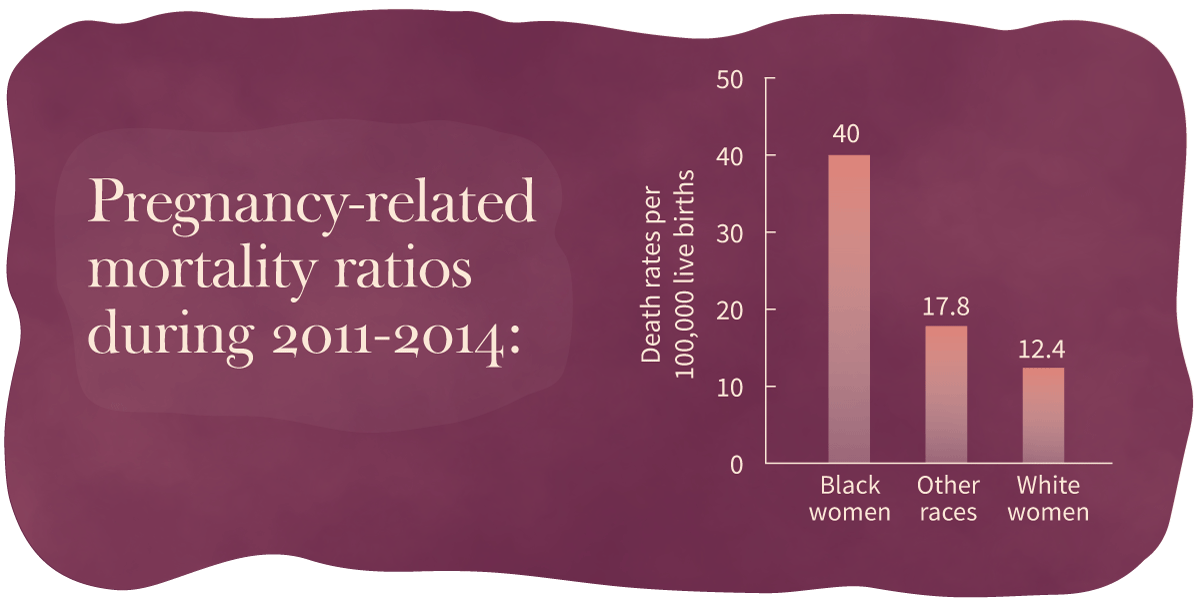

High maternal mortality rates for Black women in the U.S. are helping to drive the increases in the overall rate. According to the CDC’s Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, the rate of pregnancy-related deaths for Black women during the 2011 to 2014 period reached 40 deaths per 100,000 live births, more than three times the rate of White women (12.4) and more than twice the rate for women of other races (17.8). A 2007 study on pregnancy focused on the prevalence of five complications—preeclampsia, eclampsia, abruptio placentae, placenta previa, and postpartum hemorrhage—found that although Black and White women had similar rates of complications, Black women were two to three times more likely to die from them.

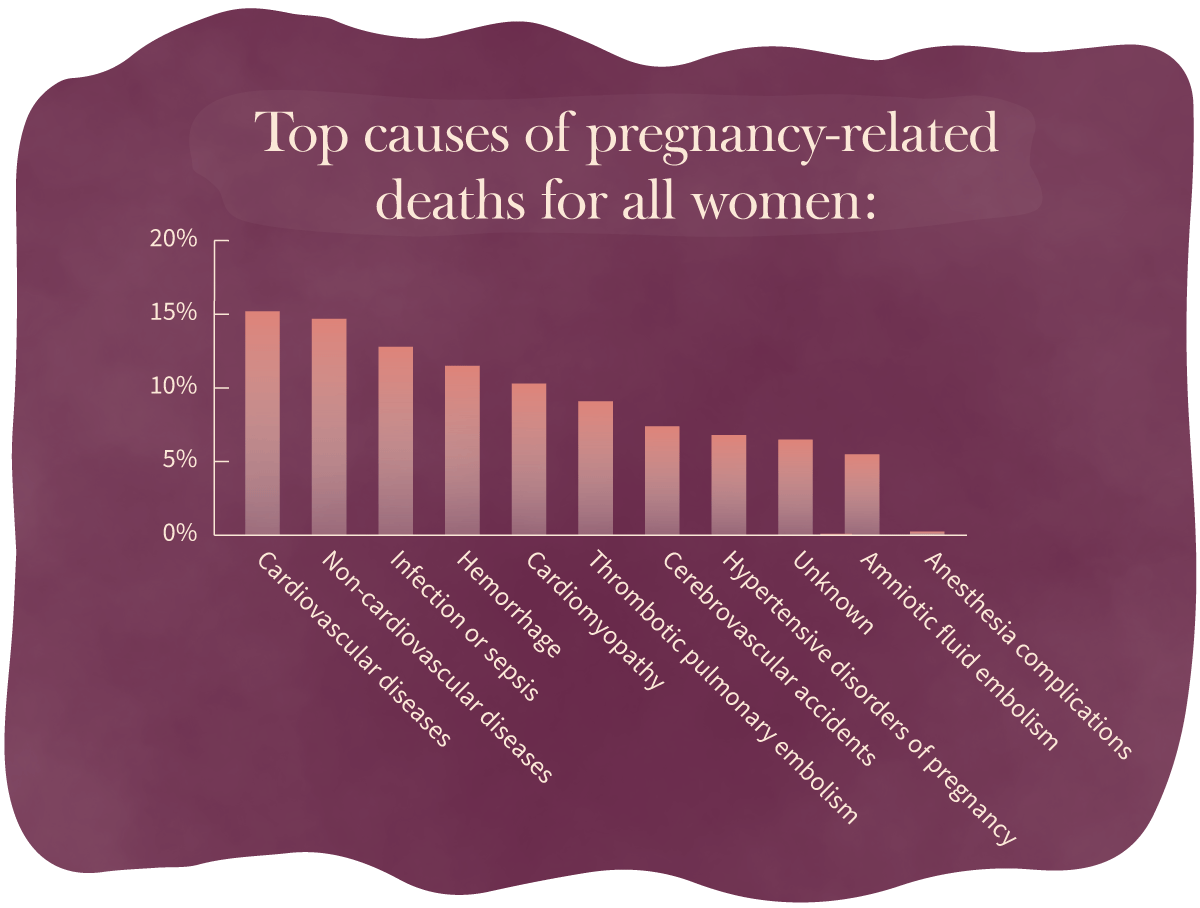

Cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular diseases are the leading causes of pregnancy-related deaths, accounting for almost 30 percent combined of all pregnancy-related deaths.

Go to the data at the bottom of the page about top causes of pregnancy-related deaths for all women.

Why Aren’t Black Women Getting the Care They Need?

“Broadly—and that’s a scary term, when we talk about an entire population—socioeconomic situations and circumstances that African American/Black women and women of color face may have a lot to do with it,” said Dr. Davis.

Dr. Davis points out that when health care professionals stereotype, make assumptions, and/or believe that Black women are over-exaggerating about their symptoms, these actions can leave room for dangerous health consequences if left unchecked or unchallenged.

“The concept of systemic oppression is quite real, and the reality is that everyone does not have equitable access to health care and/or resources as a result,” said Dr. Davis.

An examination of maternal and infant mortality by the Center for American Progress identified access to health insurance, providers, hospitals and maternity wards, and to reproductive health care as significant challenges for women of color. However, even when access is available, quality care and equitable treatment can be concerns.

A study on delivery funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities looked at whether the hospitals where Black and White women in New York City delivered their babies impacted pregnancy-related complications. The study found that Black mothers were not only more likely to face severe maternal morbidity (SMM)—unexpected outcomes of labor and delivery that result in significant short- or long-term consequences to a woman’s health—but also more likely to deliver at hospitals with higher rates of SMM. The study concluded that location of delivery may contribute nearly 48 percent of the racial disparity in SMM rates in New York City.

Additionally, a report from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene that looked at severe maternal mortality in the city between 2008 and 2012 highlights why racial disparities in pregnancy-related deaths and complications can’t simply be attributed to socioeconomic status. Black women who lived in neighborhoods with low levels of poverty still had higher rates of SMM than other racial and ethnic groups of women who lived in neighborhoods with high levels of poverty. Black women who graduated from college also had higher rates of SMM than other racial and ethnic groups of women who had not finished high school.

What Role Do Counselors Play?

Pregnancy takes a toll on physical health, but Black women already face a number of other chronic stressors in their everyday lives that can add to the difficulty experienced during pregnancy, Dr. Davis said. These stressors, which can include racism, discrimination, familial and environmental matters, and fiscal responsibilities, may not be the challenges that people typically associate with health, but have an impact on Black women nonetheless.

“Actual institutional and structural racism has a big bearing on our patients’ lives, and it’s our responsibility to talk about that more than just saying that it’s a problem,” Dr. Sanithia L. Williams, an OB-GYN in the Bay Area, told the New York Times. “That has been the missing piece, I think, for a long time in medicine.”

A survey on discrimination conducted by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that a third of African American respondents said they were personally discriminated against in a hospital or clinic.

“When we have conversations with Black women themselves, they say, ‘Look, I have anxiety about going to the doctor because I know that they are stereotyping me,’ ” said Jalessah Jackson, the Georgia coordinator for SisterSong, the largest reproductive justice organization in the South. “I know that they are not taking my own personal experiences within my body seriously, they are not listening to me and they are very dismissive.”

The consequences of discrimination or disbelief can be dire. One study published in 2017 that looked at 2,400 mothers who had delivered a child in U.S. hospitals from 2011 to 2012 found that mothers who perceived they had been discriminated against were twice as likely to skip postpartum visits with clinicians.

Monitoring mental health can also be an important part of pregnancy. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force noted that perinatal depression, which includes the periods during and after birth, affects one in seven women. They now recommend pregnant women and new mothers receive depression screenings. But similar to the barriers that exist for physical care, there are a number of challenges addressing mental health issues that affect some Black women during and after pregnancy.

“There are a lot of historical and contextual pieces that speak to this concept of distrust had by people of color and why there may be a lack of trust in the medical community, which counselors are essentially identified as a part of,” Dr. Davis said.

Dr. Davis says historical events like the Tuskegee syphilis experiment have resulted in distrust in the medical community that has been passed down through generations, and the mental health community could benefit from being intentional about understanding the historical reasons why people of color may choose to navigate their physical, mental, and emotional health. She also noted there is relatively little literature that examines perinatal depression among vulnerable populations and that more research needs to be done to understand this population’s unique lived experiences.

However, on an individual level, Dr. Davis said counselors have a lot to offer new and expectant mothers.

For example, mothers may need to establish a baseline for what is considered “good mental health” in order to identify potential concerns that fall outside of their norms during and after pregnancy, Dr. Davis said. Knowing the difference between “normal” sadness or anxiety can be helpful when determining whether additional steps need to be taken or when to seek professional help.

“Not being aware of what is one’s concept of normalcy may cause heightened reactions rather than being proactive,” said Dr. Davis. Counselors, she said, can offer support in a variety of ways including helping mothers understand their emotions and normalize these new experiences.

Six Ways Counseling Can Help New and Expectant Mothers

Dr. Tonya Davis, assistant director of clinical training for The Family Institute at Northwestern University’s Counseling@Northwestern External link program, shares how counselors can support pregnant women.

- Help women understand the changes going on in their bodies.

- Help women understand the changes in their minds as they relate to emotions.

- Normalize experiences that may be new to women, allowing them to adjust to changes.

- Find a sense of normalcy of what their family looks like now and what it will look like.

- Conceptualize what their new role of mother will look like and operationalize the concept of being a mom.

- Work through their expectations of pregnancy and motherhood versus the realities.

But knowing the benefits of reproductive counseling may not be enough. Dr. Davis points out that there are a variety of reasons some Black women may hesitate to reach out to a counselor. Some may turn to religion and spirituality, rather than choosing counseling as a first line of defense for mental or emotional concerns.

“Black women could be fully aware of the role and dynamic of counseling, but it may not have a much-needed sense of credibility to pursue that route,” Dr. Davis added. “Is there a lack of interest and/or trust in the counseling process? It would not be uncommon for Black women to believe that counseling is not the ‘magic wand’ that is going to help or fix their mental or emotional ailments.”

How Can Counselors and Other Health Professionals Break Through?

Darline Turner, founder of Mamas on Bedrest and Beyond, which provides prenatal support for women with high-risk pregnancies, is trying to find solutions for mothers. She hosts “Moms’ Luncheons,” where participants have lunch, bring their kids, and are provided a space to talk about their problems. Some of the facilitators are therapists.

“It is in a context that is not so threatening, because the stigma is huge,” Turner said.

Turner also founded the Healing Hands Community Doula Project, a support system for pregnant women of color and a resource center to connect them with medical services suitable to their needs.

“One of the reasons I started the community doula program is because when you see people that you know from your community, you are more likely to trust that person. You do business with those who you know, like, and trust,” said Turner, who emphasized the importance of providers spending time at community events to understand the populations they serve.

Dr. Davis says counselors need to do the same.

“We need boots on the ground to get a feel for what is going on in the area, who is in the area, what people are experiencing, and what the needs may be,” she said.

Ensuring that counselors are culturally competent is also key.

“Become aware of the person sitting in front of you,” Dr. Davis added. “Don’t overgeneralize or assume. Don’t think that because you know a little something about a particular race, ethnicity, or religion that you know everything.”

Dr. Davis hopes that by creating a safe space and allowing individuals to feel valued and heard, people may also feel more invested in the counseling process, be more apt to seek services, and believe that a counselor can help them achieve forward movement. But she also says, “Counselors need to put more effort into being knowledgeable of self, their individual worldview, personal biases, and being intentional about understanding the worldview and lived experiences of others.”

Signs That Mental Health Care May Be Needed

Perinatal depression is common among women and may require help from a medical or mental health care professional. To prevent a problem from becoming more serious, learn how to spot signs of perinatal depression in you or a loved one.

Symptoms:

- Sadness.

- Anxiousness.

- Irritability.

- Frequent crying.

- Trouble sleeping (even when tired) or sleeping too much.

- Indecisiveness.

- Loss of interest in self-care (for example, dressing, bathing, fixing hair).

- Loss of appetite or overeating.

- Trouble concentrating or remembering things.

- Lack of interest in everyday tasks.

- Showing too much (or not enough) concern for the baby.

- Loss of pleasure or interest in things you used to enjoy (including sex).

More severe symptoms that require urgent attention include:

- Extreme confusion.

- Hopelessness.

- Seeing things or hearing voices that are not there.

- Cannot sleep (even when exhausted).

- Distrusting other people.

- Refusing to eat.

- Thoughts of injuring oneself, baby, or others.

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration

Organizations Dedicated to the Reproductive Health of Black Women

- Black Mamas Matter Alliance

- The Afiya Center

- Ancient Song Doula Services

- Black Girls Breastfeeding Club

- Black Mothers’ Breastfeeding Association

- Black Women Birthing Justice

- Black Women for Wellness

- Black Women’s Health Imperative

- Center for Black Women’s Wellness

- Mamatoto Village

- National Birth Equity Collaborative

- National Perinatal Task Force

- Restoring Our Own Through Transformation

- Shafia Monroe Consulting

- SisterLove, Inc.

- SisterReach

- SisterSong

- Southern Birth Justice Network

- In Our Own Voice: National Black Women’s Reproductive Justice Agenda

Organizations Dedicated to the Reproductive Health of Women

- Center for Reproductive Rights

- Guttmacher Institute

- MomsRising.org

- National Advocates for Pregnant Women

- National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health

- National Women’s Health Network

- National Women’s Law Center

- Planned Parenthood Federation of America

- Power to Decide

- Reproductive Health Access Project

- The Seleni Institute

The following section includes accessible data from the graphic in this post.

Causes of Pregnancy-Related Deaths↑

| Cause of Death | Percentage of Pregnancy-Related Deaths |

|---|---|

Cardiovascular diseases | 15.2% |

Non-cardiovascular diseases | 14.7% |

Infection or sepsis | 12.8% |

Hemorrhage | 11.5% |

Cardiomyopathy | 10.3% |

Thrombotic pulmonary embolism | 9.1% |

Cerebrovascular accidents | 7.4% |

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 6.8% |

Amniotic fluid embolism | 5.5% |

Anesthesia complications | 0.3% |

The cause of death is unknown for 6.5 percent of all 2011–2014 pregnancy-related deaths.

Citation for this content: Northwestern University’s online Master of Arts in Counseling program.